“He is a much abler man than I thought him,” commented one US Senator from Pennsylvania

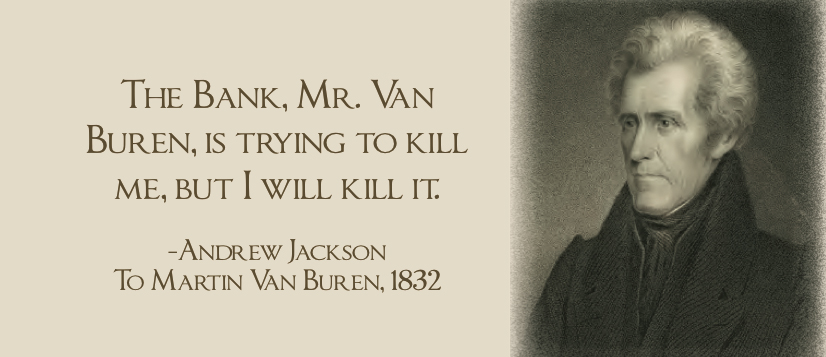

Andrew Jackson, genuine American hero, enjoys an iconic, champion of the common man reputation, earned strictly on merit. He is perhaps best known today as a highly distinguished military general and two term president. And of course there is that face on the $20 bill. How did it get there?

Like most of us, the colorful Andrew Jackson was not the Senator’s son. Rather, he was the epitome of a self made man. His father had died before Jackson was born, in the year 1767. When he was still very young, Jackson's mother left him and his older brother to care for the Revolutionary War soldiers, who had been wounded in action and were convalescing. As a result, he had grown up as an orphan, on his own.

Andrew Jackson, genuine American hero, enjoys an iconic, champion of the common man reputation, earned strictly on merit. He is perhaps best known today as a highly distinguished military general and two term president. And of course there is that face on the $20 bill. How did it get there?

Like most of us, the colorful Andrew Jackson was not the Senator’s son. Rather, he was the epitome of a self made man. His father had died before Jackson was born, in the year 1767. When he was still very young, Jackson's mother left him and his older brother to care for the Revolutionary War soldiers, who had been wounded in action and were convalescing. As a result, he had grown up as an orphan, on his own.

During the Revolutionary War, a British

soldier arrogantly demanded that the young boy get down on his knees and clean

the soldier’s boots, immediately. At the

time, he was but age 13 and quite impressionable. When Jackson refused to obey the order

on grounds that he was a prisoner of war, the soldier lashed out at him with

his sword. Jackson Jackson

Later, at age 39, already having achieved the military rank of General,

Understanding this, together with his second, he devised a plan. The two calculated that the only way he could survive the duel, and win, was to let his adversary draw first and hope that the wound inflicted upon him would not be fatal. Amazingly, the plan worked. His adversary’s quick shot had shattered two of

The bullet in

What set

Andrew Jackson’s most distinguishing physical feature was his bright, deep, blue eyes, which could shower sparks when passion seized him. Anyone could tell his mood by watching his eyes; and when they started to blaze it was a signal to get out of the way quickly. But they could also register tenderness and sympathy, especially around children, when they generated a warmth and kindness that was most appealing. Unfortunately, the artist's depiction on the $20 bill offers the ordinary citizen but a tantalizing glimpse.

-Michael D’Angelo