For those old enough to remember, scenes from Baltimore conjure up images from the 1960s, standard-bearer for racial unrest in the modern civil rights era. Were the Baltimore riots (and events perhaps yet to come) the result of the mistreatment of just one man? Or is there more involved? As the national economy ebbs and flows, prosperity in this age of acquisitive individualism appears to have bypassed Baltimore’s inner city neighborhoods, which remain largely unchanged in 50 years.

Why did they riot in Baltimore? Why did they riot in the 1960s? Are events related?

The 1960s riots took place in the Watts

section of Los Angeles , as well as several other

major northern US cities,

including Chicago , Detroit ,

Milwaukee , Washington ,

D.C. and Newark . The riots were not confined to the US ,

however. Great

Britain and South Africa

also experienced race riots during this time.

The riots had

begun in 1965, due to mounting civil unrest, and continued for three successive

summers. President Lyndon Johnson appointed a federal commission on July 28,

1967, while rioting was still in progress.

He determined to learn the

cause of the race riots and unrest. Upon signing the

order establishing the commission, the president asked for answers to three

basic questions about the riots: “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening

again and again?”

The commission’s

final report, named the Report of the

National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, or Kerner Report, was released on February 29, 1968, after seven months of investigation. The

426-page document became an instant best-seller, with over two million

Americans purchasing copies. Its basic

finding was that the riots resulted from black frustration at lack of economic

opportunity. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

critiqued the report a “physician’s warning of approaching death, with a

prescription for life.”

One of the commission’s core findings was

that the federal government had engaged in unfair and discriminatory loan

practices. For example, in important

matters of employment, education and housing especially, federal low interest

loans under the GI Bill were made available to World War II and Korean war

veterans who were white, as an incentive to flee to the “safety” of the

suburbs, where a better quality of life awaited. Black veterans were illegally denied equal

treatment under the law.

The Kerner Report’s

most infamous passage warned, “Our

nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white --- separate and

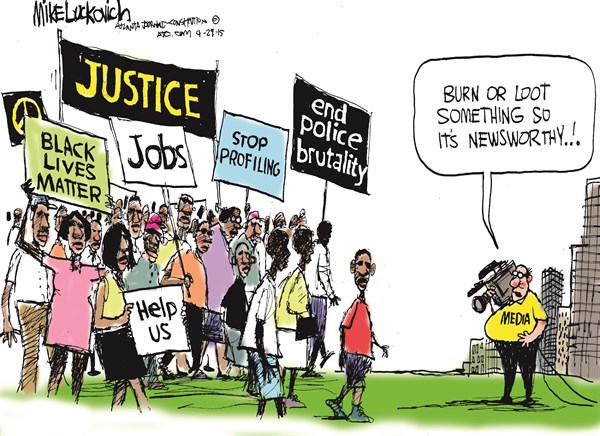

unequal.” The report berated

federal and state governments for failed housing, education and social service

policies, also aiming some of its sharpest criticism at the mainstream media:

“The press has too long basked in a white world looking out of it, if at all,

with white men’s eyes and white perspective.”

The federal commission concluded that the

riots were the result of poverty, police brutality, poor schools, poor housing,

attributed to “white racism” and its heritage of discrimination and

exclusion. The equation was a simple

one: no education, no job, no housing and no political power equaled no hope.

The federal commission concluded that the

riots were the result of poverty, police brutality, poor schools, poor housing,

attributed to “white racism” and its heritage of discrimination and

exclusion. The equation was a simple

one: no education, no job, no housing and no political power equaled no hope.

Following the riots of the 1960s, America ’s

suburbs continued a trend of becoming more white and its cities more

black. This phenomenon occurred as much

in the North and on the West Coast (Newark , Detroit , Chicago , Philadelphia , Trenton , Camden , Cleveland , Oakland and Los Angeles ) as

in the South (Atlanta

and Charlotte).

The Johnson

administration had the report analyzed but dismissed its

recommendations, however, on budgetary grounds. Soon the Great Society would be sidetracked anyway by external events in a far away place called Vietnam

Is this some of what's going on --- and not going on --- in Baltimore?

Is this some of what's going on --- and not going on --- in Baltimore?

-Michael D'Angelo