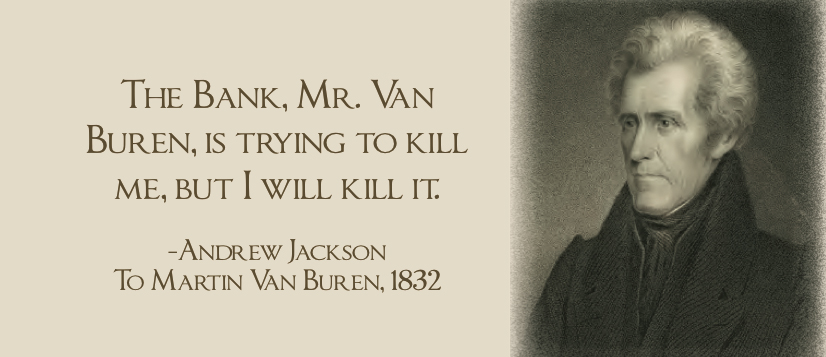

“The

bank, Mr. Van Buren, is trying to kill me, but

I will kill it.” Andrew Jackson addressed his future vice president very quietly, without any passion or tone of rage. Nor was it a boast. Just a simple statement of fact. …

October 2013 brings the ordinary citizen face to face with yet another economic crisis, this one self-inflicted. A threatened refusal by Congress to honor obligations already incurred finds the government on the brink of default for the first time in US

The status quo is born of the larger,

desirable idea of a common culture or identity.

Hard earned and built with the blood and sweat of prior generations, the

culture evolves deliberately. It cannot,

must not, be casually discarded. But on uncommon

occasion the status quo breaks down, and change becomes necessary. What happens

then? Does anyone realistically expect

that the status quo will not push back? A comforting

fact is that today the ordinary citizen is not

alone. We have faced these demons

before.

The nation’s early days featured a period known as the Era of Good Feeling (1816-1824). It was marked by a rare absence of partisan

conflict. At the same time widespread

corruption began to infiltrate and plague many American institutions. Andrew Jackson saw that period not as an Era

of Good Feeling but rather as the Era of Corruption.

No institution at the time was perhaps more corrupt than the Bank of the United States (BUS), which had been the sole, central banking institution in the nation. The BUS was a banking monopoly, headed by a director who was the subject of a political appointment, not answerable to the electorate. It was discovered that many Congressmen were on open “retainer” to the BUS, and as such more than eager and willing to do its bidding.

No institution at the time was perhaps more corrupt than the Bank of the United States (BUS), which had been the sole, central banking institution in the nation. The BUS was a banking monopoly, headed by a director who was the subject of a political appointment, not answerable to the electorate. It was discovered that many Congressmen were on open “retainer” to the BUS, and as such more than eager and willing to do its bidding.

Andrew Jackson had

articulated the fundamental doctrine of Jacksonian Democracy long before his election to the presidency in 1828:

The obligation of the government to grant no privilege

that aids one class over another, to act as honest broker between classes, and

to protect the weak and defenseless against the abuses of the rich and

powerful.

President Jackson saw the danger and

corruption inherent in the set up of the BUS.

He argued that not only was the BUS corrupt but so was all of Congress for

supporting it, among other reasons.

Appealing over the head of Congress directly to the ordinary citizen, Andrew

Jackson sought to “kill” the BUS. In its

place he proposed a number of smaller, state “pet” banks to promote competition

and fair play.

Not surprisingly, the Congress whose members

were financially reliant on the BUS fought bitterly to oppose its demise. The BUS quickly brought on economic depression which was

well within its power, occasioning tremendous hardship upon the ordinary

citizen. At the same time the BUS issued an ultimatum carefully disguised as a media campaign.

It told the ordinary citizen that all President Jackson had to do was

abandon his efforts to kill the BUS. The depression

would then lift and things return to “normal.”

The battle became so vicious that the

Congress went so far as to publicly censure the president for his actions on

the road to the demise of the BUS. An undeterred Jackson sought to make the

issue of whether to re-charter the BUS the central issue of his re-election campaign in 1832. His advisors said the

issue was too hot, too risky, that any action as to the national bank’s

continued existence should come after the election. Jackson ignored them. He gave the ordinary citizen a clear choice,

challenging him to vote either for Jackson or the BUS.

Of course, and as always, the ordinary citizen sustained Jackson, the BUS suffering its ultimate demise in

the name of necessary reform. A

thoroughly embarrassed Congress was left with no alternative but to revoke the

president’s censure and issue in its place a resolution of public gratitude.

The

banking crisis left an enduring moral impression on the national conscience. It also capped a fascinating period in American history. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the

The

banking crisis left an enduring moral impression on the national conscience. It also capped a fascinating period in American history. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the

Returning to the present, it matters little that two national elections with affordable health care as a featured campaign issue have been lost, as efforts to “repeal and replace” similarly failed. And it matters little that a conservative-leaning US Supreme Court has also reviewed the law and found it to be constitutional.

The present crisis finds an entrenched but failed status quo seeking to destroy the 2010 Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration’s signature legislative achievement, by de-funding it. The ultimatum is similarly orchestrated. If the president would only accept delay in implementing the provisions of affordable care, the ordinary citizen is told, everything will be fine. The approach cannot be appreciably distinguished from the bank robber who instructs the teller: “Put your hands up, do as I say, and nobody will get hurt.” It's a last ditch effort in death spiral.

In the process of attempted political blackmail, who knows what dark times may yet await the ordinary citizen? But the similarities to Andrew Jackson's dealings with the BUS are unmistakable, the result to come perhaps no less fundamental.

The present crisis finds an entrenched but failed status quo seeking to destroy the 2010 Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration’s signature legislative achievement, by de-funding it. The ultimatum is similarly orchestrated. If the president would only accept delay in implementing the provisions of affordable care, the ordinary citizen is told, everything will be fine. The approach cannot be appreciably distinguished from the bank robber who instructs the teller: “Put your hands up, do as I say, and nobody will get hurt.” It's a last ditch effort in death spiral.

In the process of attempted political blackmail, who knows what dark times may yet await the ordinary citizen? But the similarities to Andrew Jackson's dealings with the BUS are unmistakable, the result to come perhaps no less fundamental.

-Michael D’Angelo